Puerto Rico Sugar Industry

The main reason to document the sugar industry is the fact that for approximately three centuries, the sugar industry was the main contributor to the economic development of the whole Caribbean area, from Cuba, the largest and northernmost of the Greater Antilles to Trinidad, the southernmost of the West Indies. From the 17th Century until the mid 20th Century, sugar was at the center and the main contributing economic activity in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti and most of the West Indies. Sugar was an attractive commodity and an important source of revenue and wealth for the settlers and the colonist nations. During those years, there were periods of prosperity and stagnation, the latter mainly due to wars, competition from beet sugar manufacturing in Europe, over production, market price fluctuations, world economic events, tariffs, quotas, plagues, abolition of slavery and labor issues. The sugar industry began to expand in the Caribbean and the West Indies after the founding of the Thirteen Colonies when that new market opened.

When there was no more gold to mine shortly after its discovery by Christopher Columbus in 1493 until the latter part of the 19th Century, the Puerto Rican economy was mainly an agricultural economy. Sugar was its main subsistence product and was its main export product although trading was mostly carried out illegally due to Spanish Crown’s restriction. As stated in the Banking Industry page, the lack of a stable currency, of a monetary system and of a banking industry capable of providing financing for its development, the Puerto Rican economy was stagnant for centuries. Until the latter part of the 19th Century when the central sugar mill concept was developed and adopted on the island, sugar manufacturing was a relatively primitive process based on small individual plantations that grew their own sugarcane and fabricated muscovado or unrefined sugar.

Spain territories in the americas were technically not colonies but viceroyalties that enjoyed the same status as all provinces in Spain and Puerto Rico did have representation in the Courts of Spain that gave the island a voice and vote in what at the time amounted to be Spain’s Parliament. Although these statements are true, Puerto Rico’s representation in the Courts of Cádiz lasted just over three years, from June 1810 until December 1813 when King Ferdinand VII returned from exile in France, rejected the Constitution of 1812 that allowed the island to be represented and imposed the monarchy again eliminating such representation. Spain had five viceroyalties in the americas, all which were arguably colonies in disguise and ended when their jurisdictions gained their independence. The Viceroyalty of New Spain which jurisdiction included Puerto Rico, ended in 1810 when Mexico gained its independence from Spain. From then on the remaining territories/colonies were administered by the Ministry of the Navy and since 1863 by the Ministry of Overseas . Being that as it may, territories or colonies, the fact is that Puerto Rico had no self government and was subject to the limitations imposed and the will of the Ministry of the Navy and the Ministry of Overseas for the most part of the 19th Century.

At the time of the US Occupation in 1898, Puerto Rico had its own autonomous government equal to that of any province in Spain. This statement though true, it was not until November 25, 1897 when then Prime Minister of Spain Práxedes Mateo Sagasta approved the Carta Autonómica of Puerto Rico alongside the Carta Autonómica of Cuba in an effort to bring to an end the Cuban War of Independence and avoid something similar to happen in Puerto Rico. The Carta Autonómica granted Puerto Rico political and administrative autonomy and opened trade with the United States and European colonies. It maintained a governor appointed by Spain who held the power to veto any decision by the local legislature he disagreed with. On February 10, 1898 Governor General Manuel Macías inaugurated the new government under the Autonomous Charter, general elections were held in March and on July 17, 1898, Puerto Rico's autonomous government began to function with a House of Representative elected by the people and a Board of Directors. All hostilities in Cuba and Puerto Rico which had been invaded on July 25, 1898, ended with the signing of an armistice protocol on August 12, 1898 that called for the cession of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Manila in the Philippines to the United States pending a final peace treaty. The signing of the armistice protocol did not allow for the local government authorized by the Carta Autonómica to operate as such but for only twenty six days. The Treaty of Paris signed on December 10, 1898 handed Puerto Rico to the United States without the island institutions being consulted.

All the above is to say and substantiate what is stated below, that the political situation of Puerto Rico as a colony/territory of Spain and especially the limitations imposed by the Spanish Crown, negatively affected and hampered the development of the island’s sugar industry and its economy as a whole during all but the last few years before the change in sovereignty in 1898 . The big boom in Puerto Rico’s sugar industry happened after the Spanish American War of 1898 when US capitalists invested heavily in the industry to satisfy increased demand from Europe and the US.

The Sugar Factory “Trapiche” Days Prior to 1873

Throughout the years, the Spanish terms Trapiche, Ingenio and Hacienda have been used interchangeably creating a great deal of confusion as to the meaning of each. Historically, a hacienda is a large estate or plantation that grew and harvested an agricultural product. Ingenio is referred to the production facilitiy of a sugarcane hacienda. Trapiche is the sugarcane grinding machinery or mill driven by blood (slaves, horses or oxen), wind, running water or steam. Since plantations of most farmers that harvested sugarcane processed their own crop, the terms Hacienda, Trapiche and Ingenio came to refer basically the same. It is worthwhile mentioning that the term blood driven mill refers to the fact it was either humans or animals that provided the force to turn the mill. The term has been many times misrepresented stating that blood driven refers to the blood spilled by slaves who got their hands and arms caught in the mills while feeding the sugarcane to the mills.

Starting in 1827 some planters turned to wind to power their mills. Trapiches powered by wind typically used a cone-shaped structure which housed the grinding machinery powered by the windmill above. Remains of six of these cone shaped structures can be seen on the Plazuela, Santa Ana, Vives, Carlota, Berdecia and La Milagrosa pages. The juice or "guarapo" extracted from the sugarcane was cooked in a series of kettles called a Jamaican Train, producing syrup or molasses and raw or muscovado sugar. The process was carried out in a stone and brick factory building adjacent to the wind mill which is clearly seen in the Hacienda Vives page. The heating process was fueled by burning wood and baggasse, therefore the need for the relatively short smoke stacks to create the needed draft. These chimneys are today the only remains of some of these sugar factories.

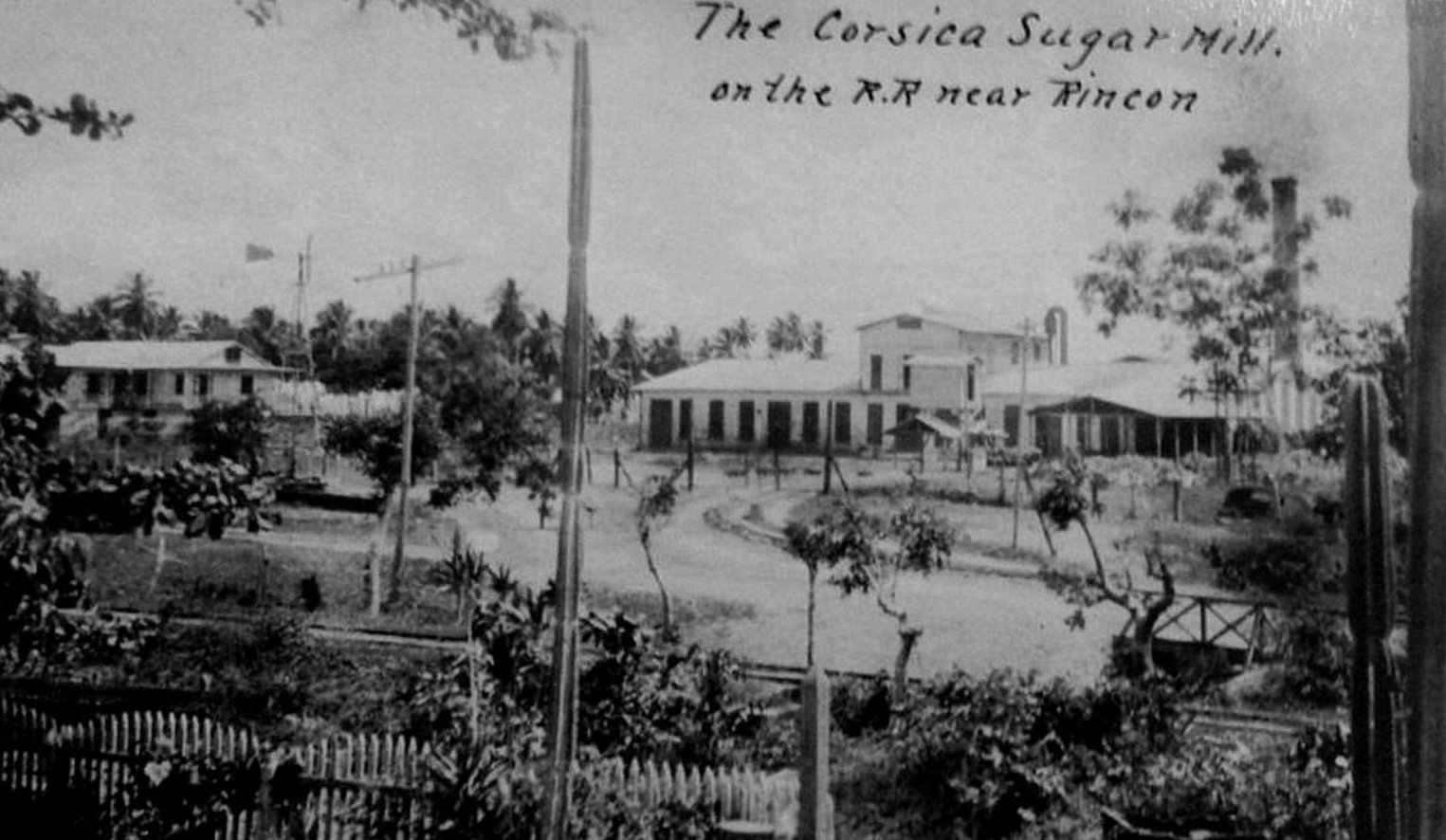

The sugar industry in Puerto Rico dates back to the early 1500s when it replaced gold mining as the island's main economic activity. It is generally accepted that the first sugar factory on the island was in the general area where today are the towns of Añasco and Rincón. It was a water run mill called San Juan de las Palmas established in the 1523 by Tomás de Castellón with 2,000 pesos lent him by the Spanish Crown. According to José Julian Acosta Calbo's notes to Fray Iñigo Abad y Lasierra 1788 book Geographical, Civil and Natural History of the Island of San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico, in 1546 Spanish Treasurer Juan de Castellanos lent 6,000 pesos of government funds for two ingenios. In 1548 Gregorio de Santaolaya built a water driven mill and two horse driven mills and in 1549 Alonso Pérez Martel received a 1,500 pesos loan from the Treasury to install a water driven mill at his hacienda. Acosta also states that in the following years the loans continued and with them new ingenios, but a short time later most ingenios were abandoned and the island, notwithstanding its fertile soil and its privileged geographical location, remained stagnant for centuries.

In 1644 Fray Damián López de Haro wrote: "All efforts in this island are directed to harvesting ginger and it is in such decline that nobody buys it, it is not even shipped to Spain; in the fields there are many farms and seven sugar ingenios where many villagers with their families and slaves help most of the year". Canon Diego Torres Vargas writings in the early 1600s stated: "...The main agricultural products in which commerce is based in this island are ginger, hide and sugar of which there are seven ingenios. Four along the Bayamón River, two along the Toa River and one water driven along the Canóbana (sic) River, that other four of which two were along the Luisa River, one in the old town and another along the Toa-Arriba River have been undone, some because of enemy invasions and others because of its owners convenience".

Fray Iñigo Abad y Lassierra (1745–1813) also states in his 1788 book: "The cultivation of sugarcane is common all throughout the island: most farmers have part of their land dedicated to this crop, but they are very few who make it their principal harvest. The large number of slaves required and the investment required to establish and ingenio with the needed machinery makes it impossible for many to increase its planting, which would be very interesting to the island and without doubt would overcome all obstacles that hamper its progress, if the extraction of its liquor would be allowed."

In 1760, Lt. Col. Tomás O'Daly Blake (1722-1781) was appointed by the Spanish Crown as chief engineer of the fortification works of San Juan, position that carried with it a generous land grant. O'Daly arrived in Puerto Rico in the summer of 1761 with two servants named Pedro Uría Flores and Joseph Iglesia, responsible for the expansion of the El Morro Fortress. In the land granted him by the Spanish Crown, by 1775 O'Daly in partnership with Bilbao native Joaquin Power y Morgán Dubernet y Hor (1725-1792), "Regidor Perpetuo de la Ciudad de Puerto Rico" or Alderman (officer charged with the government of the municipality) and slave-trade agent Alejandro de Novoa, established Hacienda Puerto Nuevo where they produced sugar and rum and were the first ones to use the Jamaican Train in Puerto Rico. As an interesting side note, Power y Morgán was the father of notable Puerto Rican Ramón Power y Girart.

While residing in the Dutch island of St. Eustatius, Tomás brother Jaime O'Daly Blake (ca.1736- ), or Jayme as the name was spelled in those days, prepared the technical blueprints needed to set up and get running Hacienda Puerto Nuevo. In 1775, he asked for a permit to reside in Puerto Rico where he intended to employ his skills and capital to help develop Tomás’ estate into a thriving sugar plantation. He envisioned it as a model for other planters, an estate that would also be capable of producing indigo, coffee and cotton while generating revenues for the Spanish Royal Treasury. On June 27, 1775, Jayme O'Daly Blake was granted a two year residential permit to live in Puerto Rico. He arrived on the island in March 1776 with Carlos Boon, his St. Eustatius native slave. Although his initial permit expired in 1777, he remained on the island a decade longer until he was finally granted status as a Spanish subject in January 1787. After Tomás death in 1881, Jayme took over ownership and the operation of Hacienda Puerto Nuevo. In December 1785, Jayme was entrusted by King Charles III with the direction of the to be established import-export business known as "La Real Factoria de Tabacos". By 1786-1787 he had also become owner of the two thousand acre Mameyes Plantation in Loiza where he raised livestock and grew rice, corn and legumes. In 1798 he acquired the prosperous Ingenio San Patricio which was adjacent to Hacienda Puerto Nuevo. The advanced technology introduced by O'Daly and the new market created after the independence of the Thirteen Colonies, allowed the island's sugar industry to start a cycle of expansion in the last twenty years of the 18th Century.

The British Seige of Havana in 1762 ended as the result of the the Treaty of Paris. Realizing that Cubans had done nothing to expel the English and concerned about their indiference towards the mother country, King Charles III commissioned Marshal Alejandro O'Reilly to visit Cuba and Puerto Rico. After his visits, O'Reilly made several recommendations to the Spanish Crown on how to deal with the colonies among which were to allow commerce with other ports in Spain besides Sevilla and Cádiz, allow slave traffic, improve the defense fortifications in San Juan, reorganize the military, increase coast vigilance to control contraband and promote agriculture, specifically the sugar industry based on the Danish model used in Saint Croix. Without a doubt, O'Reilly's recommendations were instrumental in the future development of the sugar industry in Puerto Rico.

Another important factor contributing to the development of the sugar industry in Puerto Rico was the Royal Decree of 1778 signed by King Charles III which, based on Alejandro O'Reilly recommendations, gave land ownership to those who worked it. Between 1775 and 1800, the population of Puerto Rico grew 121% from 70,260 inhabitants to 155,426 inhabitants mainly because of the increase in agricultural activity fueled by the measures taken by the Spanish Crown. This new life of the sugar industry in Puerto Rico resulted in a threefold increase in slaves between 1779 and 1802.

Almost a century later, sugar production methods at the island's haciendas were costly and inefficient and in general the end product quality was not according to standards required by the major US and British markets. Sucrose yield was only 5% when the sucrose content of sugarcane was known to be as high as 17%. The mid 19th Century decline in world sugar prices, the Cholera epidemic of 1855 which decimated the slave population, the abolition of Slavery in 1873, the limited currency in circulation and few sources of credit all negatively affected sugar production. By the time of the 1898 US occupation, coffee was the island's main agricultural export product once again.

According to Teresita Martinez Vergne in her book Capitalism in Colonial Puerto Rico, in the 1820's the number of active sugar haciendas was nearly one thousand five hundred. By the 1860's that number was considerably reduced; the then approximately five hundred fifty active sugar factories or ingenios produced 105,000 tons of muscovado sugar or 7% of the world's production. Information on page seventy six of the 1879 Guia General de la Isla de Puerto Rico, states that the number of active ingenios that year was three hundred eighty five, but by the turn of the century with the advent of Centrales, the number of ingenios was down to between one hundred fifty and two hundred, eventually completely disappearing in the early 1900s.

Between 1873 and 1880 Wenceslao Borda Rueda (1840-1914), a Colombian merchant established in Puerto Rico, Santiago McCormick owner of Hacienda Providencia in Patillas and Spanish Governor Eulogio Despujol insisted on a proposal to separate the harvesting and processing of sugarcane with the creation of factories financed by banks or foreign machinery manufacturers. This proposal was in part due to changes in the labor structure as the result of the abolition of slavery in 1873. Despite their proposal, many ingenios upgraded to steam and more modern machinery and methods to process sugarcane, increasing their sugar production and the quality of their product. However, with the advent in 1873 of the larger, more technically advanced central sugar mill concept which used advanced systems and mechanically driven machinery capable of much larger production of quality sugar accepted by the large US and British markets, ingenios started to disappear as it was more economically feasible to process their product at the nearby central sugar mill than to process it themselves.

Beginning in 1873, new central sugar mills were established with local as well as foreign capital. The Ingenio/trapiche owners had no choice but to:

merge and become part of the new centrales

abandon milling and become "colonos" just growing sugarcane under agreement with the centrales

invest in more land and advanced equipment and become centrales themselves, as was the case with Eureka and Plazuela

become cattle farms or grow other agricultural products on their lands

Many of the trapiches that at one time existed during the 1800s disappeared due to insolvency and/or consolidation, their machinery and equipment removed and sold and their structures demolished or abandoned. We have identified and photographed remains of sixty seven trapiches, each shown on its own page, their location can be identified on the sugar factories map in the maps section. Beginning in 1873 and soon after becoming a US Territory in 1898 as a result of the Spanish American War, some sugar factories grew in capacity due to modernization and/or consolidation and became central sugar mills. Humberto Garcia Muñiz in his book Sugar and Power in the Caribbean states that between 1873 and 1898, twenty seven central sugar mills were built on the island including the small island of Vieques, and between 1900 and 1920 a total forty sugar mills were built.

The Sugar Mill Days After 1873

For most of the 19th and for the first half of the 20th Centuries, sugar was the industry that most contributed to the economy of Puerto Rico. In my youth during the 1950s and 60s, you could not avoid noticing the important role the sugar industry played on the puerto rican economy at the time. Trucks and trains transporting sugarcane to the mills and the burning of sugarcane fields at night during harvesting season were constant evidence of what I thought was a vibrant industry. Little did I know, it was a dying industry. The purpose of these pages is not to tell the history of the sugar industry in Puerto Rico but to document in pictures the remains of sugar factories and central sugar mills that operated at one time or another on the island. However, as the website was being put together, I realized the need to include a brief history related to the pictures. Each sugar factory and central sugar mill for which there are existing remains is identified and documented on a separate page. The location of the central sugar millsremains on the island can be identified on the sugar mills map in the map section.

The sugar industry existed in Puerto Rico dating back to the early 16th Century. However, it was not until the 1800s that sugar production became a major agricultural product grown by "hacendados" who owned large amounts of land or "haciendas". Some haciendas became small sugar factories, also called "Ingenios" or "trapiches". These small factories processed their own sugarcane and produced muscovado sugar and molasses at onsite facilities that consisted of a mill powered by slaves, horses or oxen, called blood driven mills. It was not until the 1820s that wind driven mills and until the 1830s that steam powered mills were first introduced on the island to replace blood driven mills. The era prior to the establishment of the central sugar mill concept in 1873 is more extensively documented in the Sugar Mill and Trapiches/Puerto Rico page.

In 1870 Puerto Rico was reportedly the second largest sugar producer in the Western Hemisphere after Cuba. While Cuba is 12.5 times the size of Puerto Rico, in the period between 1848 and 1852, Cuba produced just 6 times more sugar. However, in the early 1900s, US companies and banks invested heavily in the sugar industry in Cuba and in 1924 the seventeen sugar mills controlled by the National Sugar Refining Company alone produced 452,550 tons of sugar, more than the 447,972 tons produced by all the thirty seven sugar mills in Puerto Rico.

As opposed to what happened with the Cuban sugar industry where US capitalists invested heavily prior to 1898, in Puerto Rico the only US capital investment prior to 1898 was in Central Progreso. When the island passed to being a US territory, it gained a privileged position with regards to the US tariff system. It was then that US investors opened their eyes to the new opportunities available on the island and promptly started organizing and establishing sugar mills on the island. That gave way to the incorporation of Central San Cristobal Corp., Central Aguirre Syndicate, The South Porto Rico Sugar Co. and The Fajardo Sugar Co.

Sugar production in Puerto Rico increased dramatically mainly due to these new US owned sugar mills and in a short ten years after the US occupation, sugar replaced coffee which was the principal export product of the island in 1898. Growth in sugar production was remarkable, from less than 100,000 tons in 1898 to more than 1,000,000 tons by the late 1930s. As can be seen from this Total Sugar Production Graph, between 1911 and 1952 the general trend of total sugar production in Puerto Rico had a markedly upward trend, but thereafter a precipitous decline marked the beginning of the end of the industry.

Based on this US Owned Mills vs. Total Production Graph created using production information available, and contrary to popular belief, except for six years (1926 through1930 and 1935), production of locally owned sugar mills always exceeded that of the US owned mills. It is important to note that the production increase of US owned sugar mills from 39% in 1925 to 52% in 1926 was due to the purchase of five locally owned mills by the United Porto Rican Sugar Co. and that during those six years, production of US owned mills never surpassed 53% of total production. We acknowledge though that although production of the locally owned mills was in average more than that of US owned mills, the number of locally owned sugar mills was always substantially larger than the US owned.

A general misconception regarding the US owned mills is that they controlled too much land on the island. César J. Ayala in his book American Sugar Kingdom, states that 56% of the sugarcane grown in Puerto Rico (e.i. not including that grown in the Dominican Republic) and processed at Guanica Centrale, the largest sugar mill on the island, was grown by colonos. Ayala also states that the United Porto Rican Sugar Co. owned 30,967 acres, Fajardo Sugar Co. 29,240, Aguirre Sugar Co. 24,234 and the South Porto Rico Sugar Co. 21,275. In addition to their own lands, they leased 56,000 acres resulting in control of approximately 161,700 acres or only 24% of the cropland in cane farms. This, despite the fact that colono farms produced twenty nine tons of sugar per acre in 1931-32 while company farms averaged thirty seven tons per acre. James L. Dietz in his book Historia Económica de Puerto Rico states that at the beginning of the 1930’s colonos occupied 48.7% of the land dedicated to cultivating sugarcane and produced 35.5% of the sugarcane processed. He also states that US owned sugar mills cultivated 23.3% of the land dedicated to cultivating sugarcane and produced 31.2% of the sugarcane processed in the 1934-35 grinding season while the Puerto Rican owned sugar mills cultivated 28.0% of the land dedicated to cultivating sugarcane and produced 33.3% of the sugarcane processed and that for the same grinding season, colonos supplied 29.6% of the sugarcane processed at the eleven US owned sugar mills and 40.2% of the sugarcane processed at the locally owned sugar mills.

In their book published in 2020 Agragian Puerto Rico: Reconsidering Rural Economy Society 1899-1940, César Ayala and Laird W. Bergard research and document major problems and flaws in the general narrative and historiography regarding the post 1898 extensive investment of US capital in the Puerto Rico sugar industry that "large-scale, absentee-owned sugar-manufacturing corporations acquired extensive landed estates at the expense of Puerto Rican farmers who lost their land and were gradually converted into a labor force to serve these US-based sugar companies." Ayala and Bergard document with facts and conclude that the general concensus promoted by historians, the government and the academia alike that "the development of rural landlessness, social stratification, extreme forms of inequality in the countryside, and economic dependence were all closely connected to the accumulation of large plantations by US-owned corporations, is not so."

In his essay Colonialism, Planters, Sugarcane and the Agrarian Economy of Caguas Puerto Rico Between the 1890s and 1930 its author José O. Solá states that “the historical construction of Puerto Rico as an island dominated by a handful of American sugar corporations, which in turn led to the creation of a massive sugar plantation zone where local farmers were displaced and became a new rural laboring class, is not borne out by the evidence.” He also states that “The notion that the arrival of the American troops and the opening of the American market led to widespread land dispossession in Puerto Rico is not entirely correct.”

They state that there is "an erroneous claim in much of the historical literature that US capital investments in the sugar economy led to the disappearance of between 30,000 and 50,000 small-scale landowners by the 1930s who were supposedly displaced by these absentee sugar corporations. This did not occur, according to all of the systematic data we have examined." They further state that the War Department census of 1899 indicates conclusively that there was not an extensive class of landowning small farmers on the island before 1898, a staple of nearly all interpretations of the impact of US control over the island.

Ayala and Bergard conclude that "According to our calculations, 72% of total rural families owned no land in 1899; 75% in 1935. The data radically contradict the established narrative, which revolves around large-scale dispossession of land by absentee capital and the supposed disappearance of the small-scale Puert Rican landowning class." Pedro Albizu Campos, the president of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico, repeatedly said that the island had to "reconstitute the legion of proprietors that existed before 1898". Ayala and Bergard state that what stands out in Albizu's denunciation of US colonialism is not the very real social and economic inequalities of the 1930s, but the assertion that these began in 1898, the year the United States invaded Puerto Rico. They also state that this idea of a disappeared legion of proprietors seems to have been widespread and not confined the Nationalists. They state it was pervasive across the entire political spectrum of the island as it was part of the program of the Liberal Party founded in 1932 that stated the same belief. It was also part of the program of the Popular Democratic Party established in 1938 whose slogan was "Pan, Tierra y Libertad" (Bread, Land and Liberty) and whose leader Luis Muñoz Marín governed the island from 1948 to 1964.

Samuel A. Morley in his book The Income Distribution Problem in Latin America and the Caribbean states that Latin America has always had the most unequal land distribution in the world, a legacy carried since the Spanish colonial days until today. Puerto Rico was a colony of Spain for four hundred and six years from 1492 to1898, during that period of time an agrarian structure developed characterized by extreme inequality in landownership, as was the case in the rest of Spanish America. Reading the brief write up on the pages in this website of the sixty seven sugar factories and forty six sugar mills for which ruins still exist, it is clear that the accumulation of land by the new central sugar mills, local and US owned alike, was from existing sugar estates or hacendados who already owned vast amounts of lands and not from small individual farmers.

The majority of the workers in the sugar industry were hired by local employers not by US corporations. The substantial number of colonos that cultivated sugarcane for the sugar factories employed a large number of wage workers. The locally owned mills, which as previously stated were substantially more in number and in average ground more than half of the sugarcane on the island, ground mostly sugarcane cultivated on leased lands or grown by colonos. Ayala concludes that despite the large concentration of land in the hands of the big four sugar mill companies (Aguirre, Fajardo, United Porto Rican Sugar Co. and Guanica), approximately 75% of the agricultural proletariat in the cane industry was hired by native employers.

The contribution of the sugar industry to the development of the Puerto Rican economy in the early years of the 20th Century cannot be overlooked. The September 2, 1916 edition of Facts About Sugar included an article with the heading "Porto Rico's 1916 Trade Established New Record" states:

"The Porto Rico Progress today printed the following advance survey of the island's external commerce for the fiscal year ended June 30 last, which strikingly illustrates the value of the sugar industry to Porto Rico and the important part it has played in the present record prosperity that has accrued to the people of the island and its industries during this period: Puerto Rico's external trade reached a total of $105,682,739, the greatest in the history of the island. This is a gain of approximately $23,000,000 over the previous year and exceeds the former banner year of 1912, when exports and imports were valued at more than $93,000,000 by approximately $12,000,000. High sugar prices, averaging more than $108.00 per ordinary ton for the year, as compared with an average price of $92.64 for the previous, the highest price ever before received, and an increased sugar output, were largely responsible for the big increase in trade."

The sugar industry was a wealth creator. As an example, Fajardo's earnings before taxes for the year ended July 31, 1920 was $5,456,918 or $94.73 per share on sales of $12,425,333. According to the book Economic History of Puerto Rico - Institutional Change and Capitalist Development by James L. Dietz, in 1920 Aguirre paid a dividend equal to 115% of equity. From 1923 to 1930, the return on capital of the mills owned by Aguirre, Guanica, Fajardo and the United Porto Rican Sugar Corp. averaged 22.5% per year. From 1920 to 1935 Aguirre, Guanica and Fajardo distributed $60 million in dividends to their shareholders while accumulating a surplus of $20 million. This all changed when in 1942 the Government of Puerto Rico declared the sugar mills a public utility even though there were over forty producers at the time, none of which had a monopoly. This move gave the Public Service Commission authority to limit their returns in an ill based effort to prevent capital leaving the island.

It was also the source of employment for approximately one hundred eleven thousand people. According to the 1935 census; ninety five thousand farm and sixteen thousand production workers including engineers, chemists, accountants, bookkeepers and foremen worked in the sugar industry. In 1952 the sugar industry's payroll accounted for 23% of total Puerto Rican wages. Economic activity from related businesses such as transportation, hardware stores, foundries and fuel suppliers to name a few, was also an important contribution of the sugar industry to the overall economy. It also provided for the only source of income of the many independent land owners or "colonos" whose sole activity was growing sugarcane to sell to the mills.

Puerto Rico has throughout the years been identified as one of the major rum producers in the world. Rums of Puerto Rico is a source of income not only to the distilleries but to the Puerto Rican Government as well. Based on Section 7652 of the Internal Revenue Code, most of the Federal Excise Tax on all rum imported to the US from Puerto Rico is returned to the Puerto Rican Government. According to the October 27, 2011 report by the Congressional Research Service titled The Rum Excise Tax Cover-Over: Legislative History and Current Issues, the Puerto Rican Government received over $431.7 million in Fiscal Year 2009 from this source.

The New York Times on December 14,1933 reported that the US District Court had ordered the sale of the properties of the United Porto Rican Sugar Co. which had been in receivership since February. Assets included five factories, thirty one thousand three hundred twelve acres of land, five thousand heads of cattle and about one hundred fifty five miles of railroad. In its edition of February 13, 1934 the same newspaper reported that Senator Luis Muñoz Marín had presented a resolution providing for the acquisition of the assets of the United Porto Rican Sugar Co. by the people of Puerto Rico, which sale on January 25th was still unapproved. Although this never happened, it was a hint of things to come.

Much has been said about the damaging effect of the sugar quotas imposed by the Jones-Costigan Act of 1934 which were in effect until 1959 but not in effect during the war years of 1942 to 1947. The first quota for 1934 was established based on the average of Puerto Rican sugar sold in the US for the years 1925-1933. While average sugar production during those years of 717,900 tons[1] was negatively affected by Hurricane San Felipe in 1928 and Hurricane San Ciprián in 1932, the quota for 1934 was 803,000 tons or 11.85% higher than the average used, which seems to include some adjustment for the effect of the hurricanes. As shown in the chart below, the best production year between 1911 and 1924 was 1921, at the end of the Dance of the Millions, with 470.4 tons, and it was not until 1925, the first year of the average used, when production surpassed half a million tons. There is no doubt that the quota system eliminated the prospects for growth and new investments in the industry, notwithstanding, in 1940 sugar exports accounted for 62% of the island’s total exports compared to 55.3% in 1931, although in part the percentage increase was due to a reduction of total exports during the period. As can be seen in the chart below, the difference between the quota and the actual deliveries was minimal except for 1939 when deliveries substantially exceeded the quota. The excess production was either sold in other markets and/or refined locally for local consumption.

The beginning of the demise of the Puerto Rican sugar industry can be traced to 1935 and the establishment of the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRRA) under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. The PRRA was headed by Ernest Gruening and was modeled after the "Plan Chardón" designed in 1933-34 by Carlos Eugenio Chardón Palacios, Senator Luis Muñoz Marín and Governor Rexgord Guy Tugwell to revitalize the island's economy. The plan, which never went into effect as such, specifically called for a reorganization of the island's sugar industry by redistributing arable lands from major landowners to small farmers and the disintegration of large sugar corporations into semi-public institutions. Although successful in other areas like rural electrification, the PRRA and its Plan Chardón encountered major opposition, ran out of money and in the end was not successful in restructuring the sugar industry.

This publication titled La Ruina de la Industria Azucarera is a compilation of fourteen articles published in El Mundo newspaper in 1938 by my 1st cousin 2x removed Atty. Cayetano Coll y Cuchi, one of the founders of the Puerto Rico Liberal Party in 1932. In it he argues that if the 500 acre land ownership limitation contained in the Foraker Act was implemented by virtue of the 1938 PR Supreme Court decision in People of Puerto Rico v. Rubert Hermanos, Inc., et al., the sugar industry would be destroyed and would disappear. He also wrote that it was statistically proven that the Puerto Rican sugar industry as then established did not constitute a monopoly of arable lands nor a land grabbing of the best farms but an industry that using 10% of the island's area, achieved productivity representing 80% of the island's Gross National Product. Coll y Cuchi also stated that the sugar industry had been the major contributor to the island's progress and that of its workers, whose wages tripled between 1912 and 1938.

Notwithstanding Coll y Cuchi's arguments, the government's decision to implement the 500 acre limitation that forbid corporations to own in excess of 500 cuerdas[2], which provision had been always overlooked and never enforced, was indeed the last nail in the coffin for the sugar industry. In 1937 the government decided to enforce the 500 cuerdas provision of the law in a series of legislative maneuvers that went all the way to the US Supreme Court. This action by the government negatively affected the operations of the larger US as well as locally owned sugar mills by taking away their control over the sugarcane supply and limiting their quality control in the fields.

The Puerto Rico Land Authority created in 1941 to "acquire and preserve land with high agricultural value and facilitate the use of these lands for the benefit of the people of Puerto Rico", was really created to acquire the excess land over 500 acres owned by the sugar mills, most of it which has not been cultivated since. In 1974, the Corporación Azucarera de Puerto Rico or Sugar Corporation of Puerto Rico was created to "save" the sugar industry. In its efforts, the Sugar Corporation acquired most of the sugar mills and sold their machinery in Latin America while continuing to run a few. But, as is the case with basically all government run institutions, the government run sugar mills were unsuccessful and eventually all had to shut down.

Notwithstanding the importance of the sugar industry in the island's economy, it was allowed to die. It is inconceivable to understand how the sugar industry was allowed to completely disappear when today, sugar needed for local consumption and molasses which fermentation is needed to make the alcohol required for rum production and at one time both local products, have to be imported. There are many opinions regarding the true reason(s) for the demise of this one time king, some of which carry more weight than others. In 2012 the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis published a study which in my opinion clearly explains the true reasons for the industry demise. The study titled What Ever Happened to the Puerto Rican Sugar Manufacturing Industry? concludes that it was not necessarily the poor performance of the Puerto Rican economy that caused the industry to fail, but local government policies.

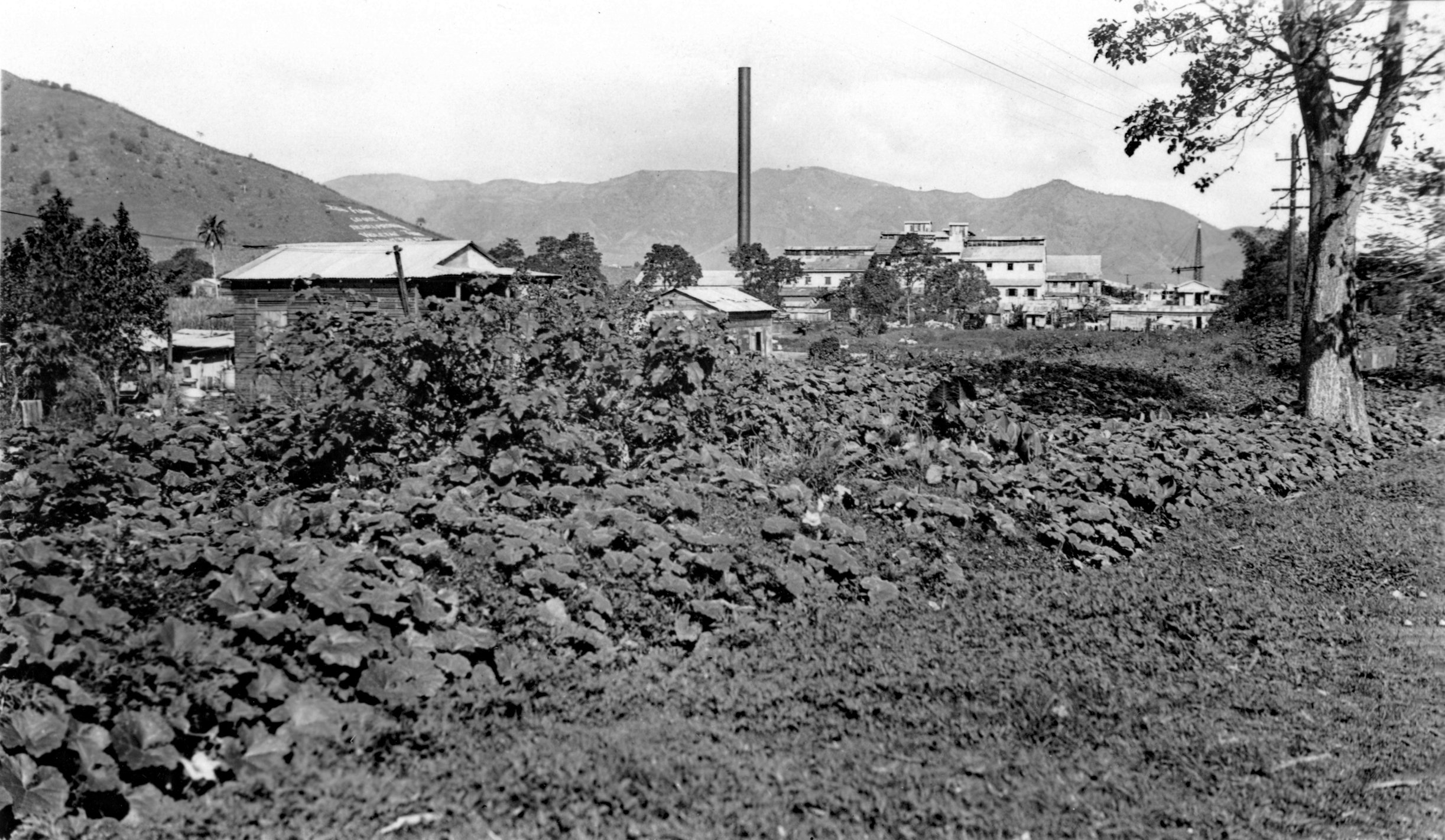

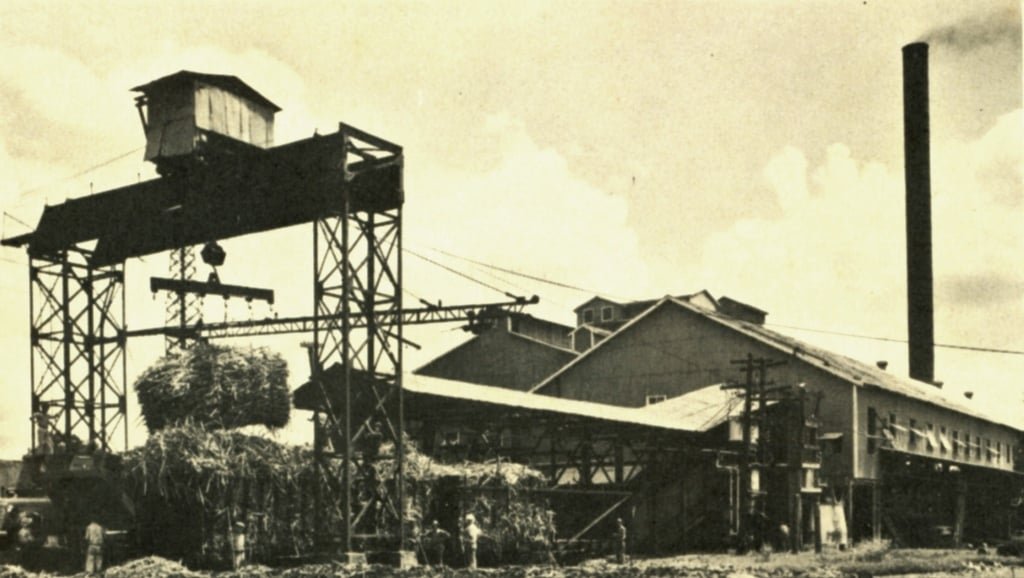

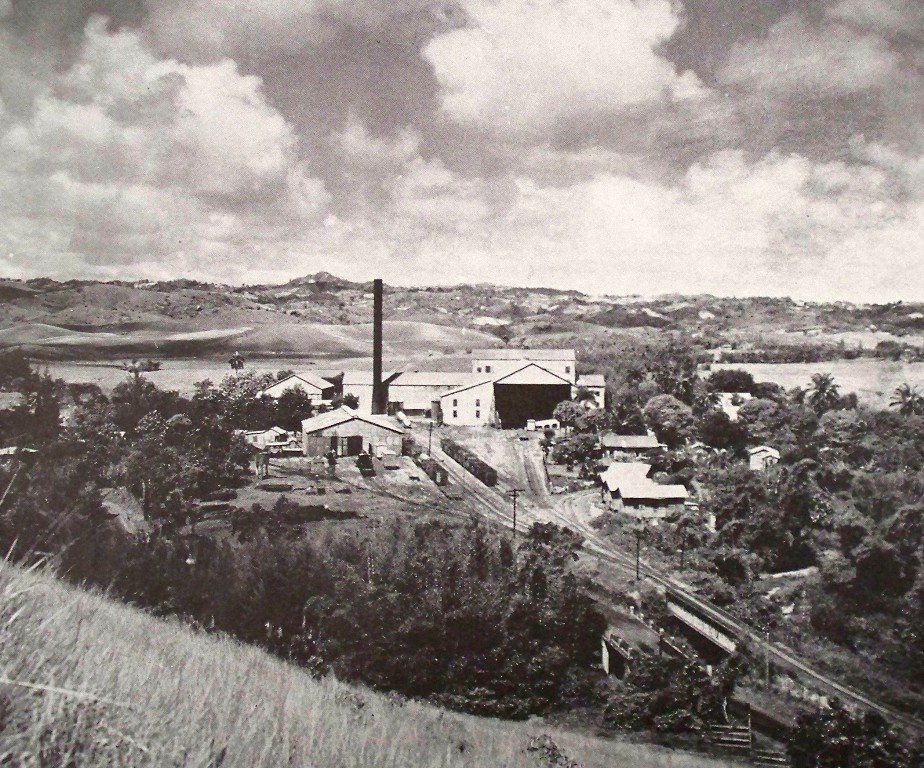

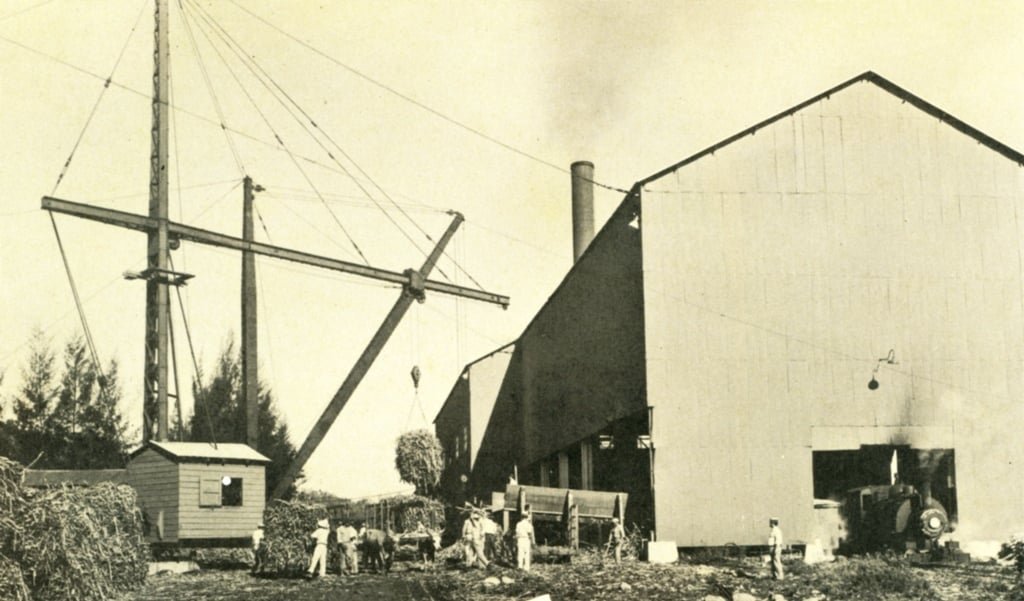

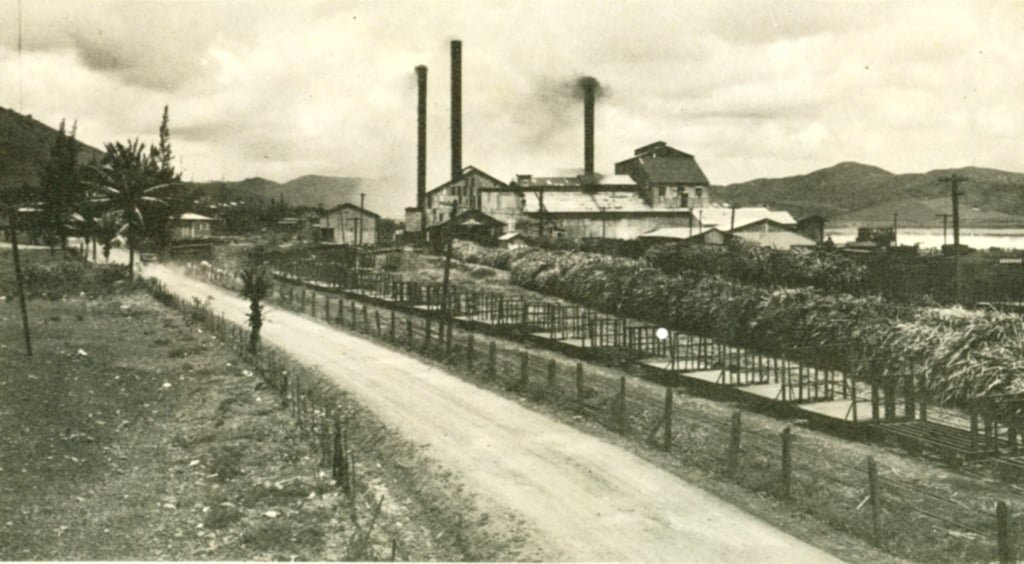

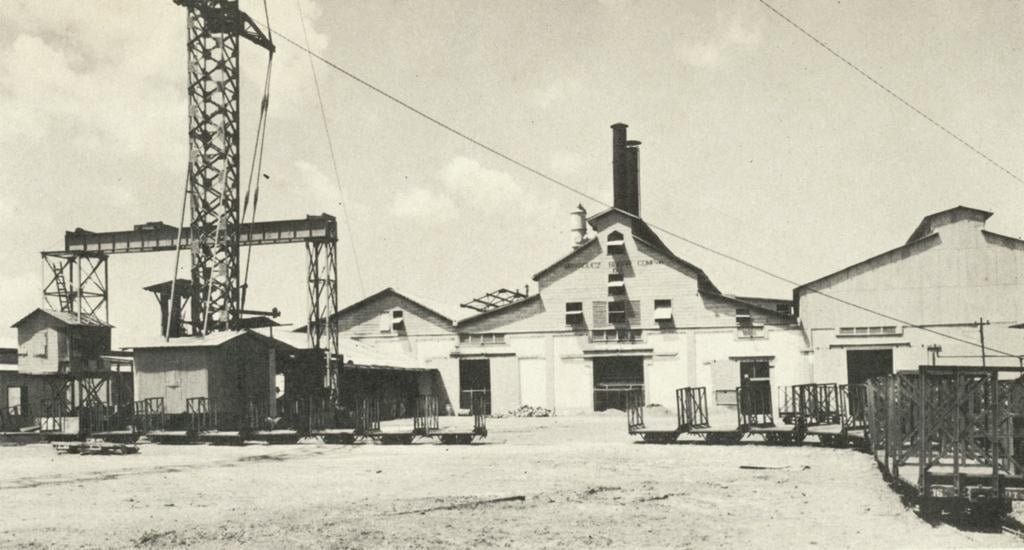

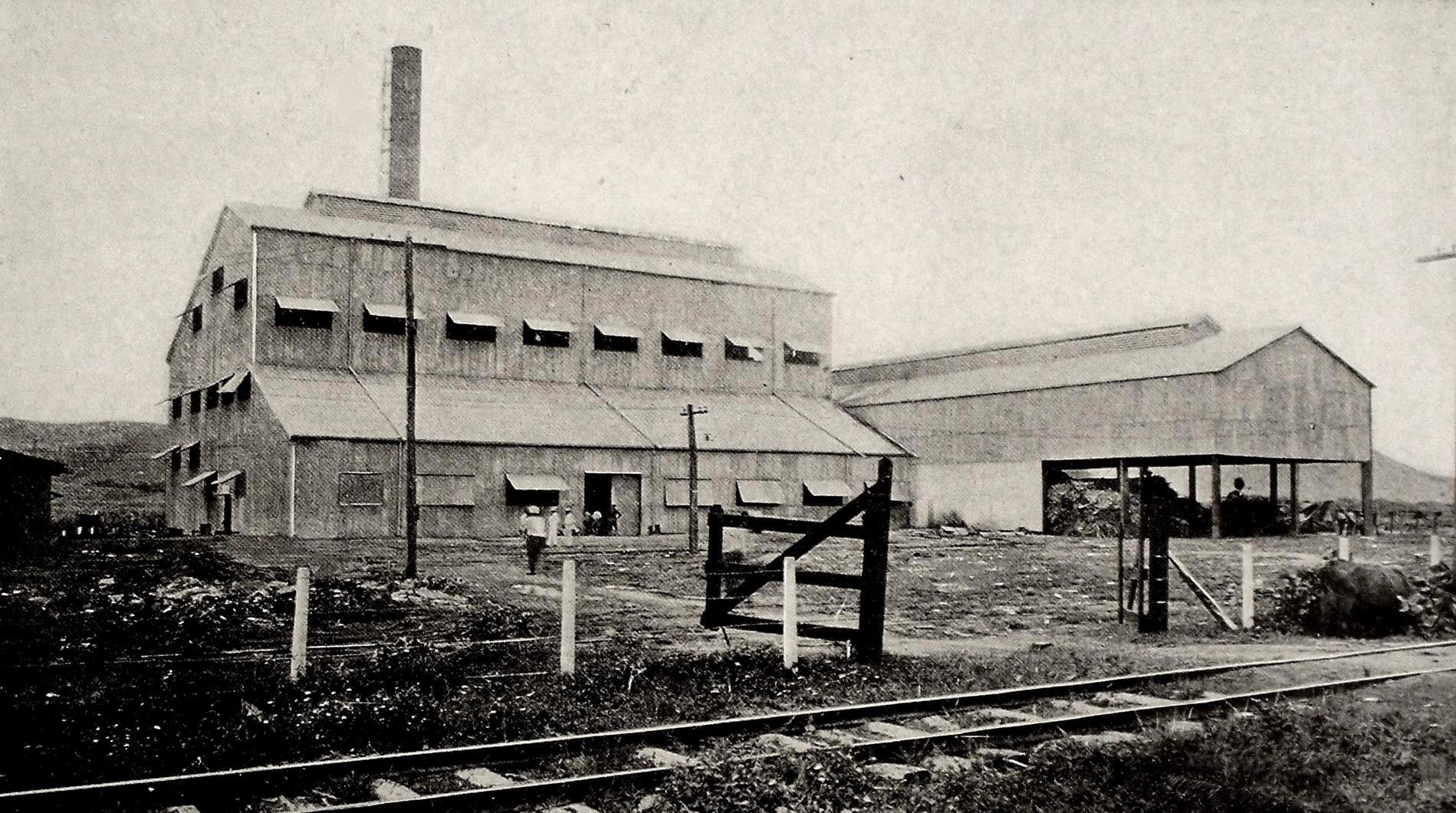

The gallery below is of sugar mills that at one time existed on the island, have completely disappeared and there are no remains of them left.

_______________________________________________________

[1] Tons refer to short tons of 2,000 pounds.

[2] One cuerda equals 0.97 acre.

Tons (000)

Tons (000)

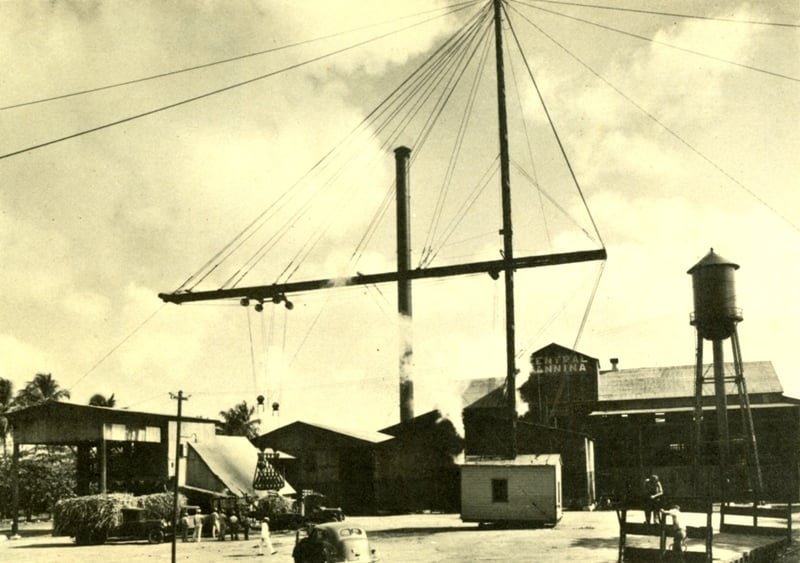

Central Constancia - Ponce

Central Defensa - Caguas

Central Defensa - Caguas

Central El Ejemplo - Humacao

Central Esperanza - Vieques

Central Herminia - Villalba

Central Juanita - Bayamón

Central Pasto Viejo - Humacao

Central Rochelaise - Mayagüez

Central San Cristobal - Naguabo

Central San Miguel - Luquillo

Central Triunfo - Naguabo

Central Vanina - Rio Piedras

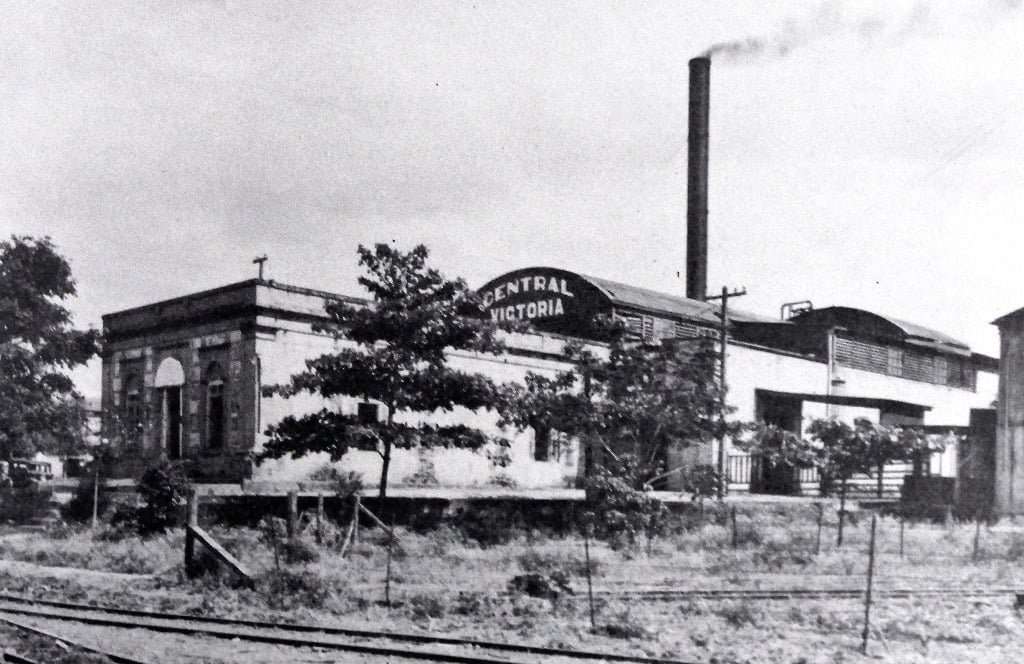

Central Victoria - Carolina

Central Corsega - Rincón